Published on February 17, 2010

Getting here had been quite a struggle – Was the Myanmar-Thai border open where we wanted to cross? Could we get a visa at the border? Was there public transport to the border posts? – endless unanswered questions. So it was with significant disappointment that my friend and I, having overcome all these hurdles entering Myanmar, realised we’d seen the whole village of Payathonzu in less than two hours.

We sat down to an herbal-tasting, bland-looking cup of tea, somewhat despondent with the trip so far. The day had started in such a promising fashion, riding in the back of a pick-up truck, surrounded by a wicked group of Myanmar women chewing betel nut and smoking what looked like huge spliffs. They spent the ride chattering away and having a good laugh, before running off without paying their fare, much to the Thai driver’s dismay. After such an introduction to all things Myanmar, Payathonzu seemed just a tad tame. Little did we know what the day had in store.

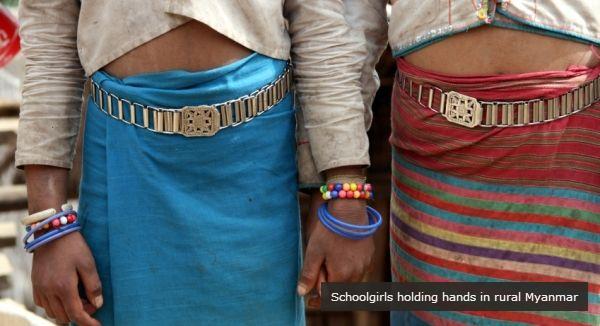

The village did not appear to have much to its name. There was what seemed to be, a monastery, on the outskirts, which we decided to visit. Ambling on, we happened upon a school, part of the monastery, with classes in full swing. Being the only Westerners in the neighbourhood – and the only ones to pass through that particular border crossing in a month – the head teacher ran out to greet us in excitement. He was in the midst of giving an English lesson and asked if we would care to join in. The poor man clearly needed some time off from the large group of students and soon we’d been roped into giving the whole lesson in his stead.

The earlier hours spent languishing in Myanmar was a stark contrast to the whirlwind of accidental volunteering activity. We took time to get every single child to say something in English. What a stern, shy, unsmiling lot they seemed in class, but come break-time they were running around, shouting and playing like ordinary, happy kids. The teacher, who spoke reasonable English and had previously lived in the capital, took us out for coffee (thank heaven no more of that nasty tea).

He explained the children were orphans, living and studying at the monastery, in the care of the monks. Suddenly we’d been given the chance to actually make a difference on our journey and connect with the locals on a completely different level. After the English lesson we snuck off to the village market, where we’d earlier seen a world map. We purchased the map and donated it to the school for their geography lessons.

The head teacher then introduced us to the local midwife and the town’s doctor, who invited us to his clinic with its endless queue of patients. Unfortunately all he had to offer them were the empty shelves in his medicine cabinets. The daily difficulties of living in rural Myanmar were profoundly evident.

With the sun beginning to set, our day in Myanmar was coming to an end. As our one-day visas were soon to expire, we reluctantly made our way back towards Thailand. Just a single day of volunteering in Myanmar had proved an invaluable experience, hopefully also making a difference to the children we met at the monastery. The insights we gained into daily life in Myanmar, including its hardships, are memories that will remain. If one day can be that inspirational, it’s enough to make me consider volunteering for much longer. There are many such opportunities across Myanmar and other parts of Southeast Asia, some informally arranged and some through volunteer organisations. If you do go the less formal route, try to ensure the job you’re taking couldn’t just as easily have been carried out by a local resident.

There are several international organisations which arrange voluntary work in Myanmar on a more long-term basis: www.volunteerabroad.com and www.sstmyanmar.com, are two among others.

Anna Maria is a freelance travel and food writer, based in London, UK. She has travelled extensively in Southeast Asia and Latin America, recently co-authoring the new Footprint guide to Mexico.