Published on December 16, 2009

On a recent visit to Dal, an ethnic Jarai minority village in Cambodia’s Ratanakiri Province, I had a moment of enlightenment. Standing guard outside one of the tombs in the village cemetery was a familiar effigy – a wood carving of a man squatting on his haunches, hands wrapped around the knees.

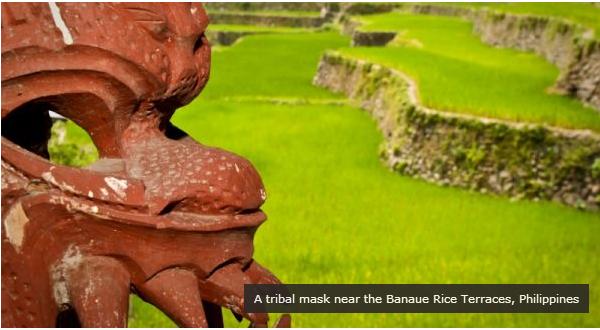

It bared striking resemblance to a bulol – the ubiquitous wood carving sold in souvenir shops in the Philippines. Bulol are traditionally used to “guard” the rice terraces of various hill tribes of North Luzon (Philippines). The most famous bulol carvers are the Ifugao, the masterminds of the UNESCO-listed Banaue rice terraces. The ancestors of the Ifugao are thought to have migrated from Vietnam less than 15,000 years ago.

It turns out that Dal, lies less than 30km from Cambodia’s border with Vietnam. Suddenly it made sense why I was staring at an apparent replica of a Philippine bulol.

Besides the general poverty, lack of electricity and preponderance of pigs running about, more similarities quickly became apparent as I entered the village; the sambot (skirts) worn by women were very similar to the wraparound tapis skirts worn by the hill-tribe women of North Luzon; children and adults were toting vegetables from the field in beautiful woven baskets strapped to their backs; toothless elders smiling through Betel-ravaged gums.

Many customs, too, seemed familiar. As in North Luzon, wealth is gauged by the number of pigs and water buffalo you own. Seminal events – marriage, death, the start of the rice planting and harvest seasons – are marked by animal sacrifice. True, these customs are common in ethnic minority villages throughout Southeast Asia, not just in the Philippines. Still, I couldn’t help but marvel that so many cultural similarities persevere several thousand years after the Ifugao and other Luzon hill tribes departed mainland Southeast Asia.

The most obvious difference between Cambodian and Philippine ethnic minorities is that while most Philippine tribes have converted to Christianity (mainly) or Islam (in parts of Mindanao and the south), Cambodian tribes remain largely animist. Yet this seems to have less of a differentiating effect than one would think, as Philippine tribes have incorporated pagan traditions into their Christian or Muslim rituals.

And some elders in the hill-tribe communities of North Luzon do remain strictly animist – not surprising if you consider that they were only Christianized by the Americans in the first half of the 20th century (lowland areas were converted by the Spanish centuries before this). In fact, North Luzon hill tribes still engaged in the decidedly unchristian practice of headhunting as recently as 50 years ago. In the remote province of Kalinga, the last living Filipino headhunters proudly display their tattooed chests, each horizontal line denoting a kill.

In both Cambodia and the Philippines, ethnic minorities face a gaggle of threats, ranging from land grabs by logging and mining interests to the gradual erosion of cultural traditions as the modern world encroaches. These problems seem much worse in Cambodia, if only because its indigenous population is tiny compared to that in the much larger Philippines.

Cambodia’s minority tribes are found almost exclusively in the northeastern provinces of Mondulkiri (with just one main tribe, the Pnong) and Ratanakiri (with about seven tribes). Both provinces are rapidly opening up to tourism. Even the purest Cambodian minority villages – where women still walk around topless, male elders wear loin cloths, and children as young as five walk around smoking tobacco pipes – are remarkably easy to reach. A bumpy motorbike ride or a short river trip out of the provincial capital does the trick. Tourists need to tread softly in these areas. Always visit the village chief upon arrival, respect cultural traditions, and don’t take photos without permission, which will rarely be granted unless you spend quality time in the village bonding a bit with the locals.

The Philippines offers an altogether different experience. The country is home to scores of distinct tribes. In addition to the highland tribes of North Luzon and Mindanao, there are pockets of extremely primitive aboriginal tribes (known, generally, as Negrito) scattered across the archipelago. While most highland tribes have assimilated to some degree into Western culture, in more remote provinces, such as Kalinga and central Mindanao, you’ll still find indigenous communities living almost as they did hundreds of years ago. It takes some work to get to these communities – usually a day in a bus followed by at least a half-day walking. But the rewards are definitely worth it.

Greg Bloom is a freelance writer living in Phnom Penh. He previously lived in the Philippines for five years, and has contributed to Lonely Planet guidebooks for both countries.